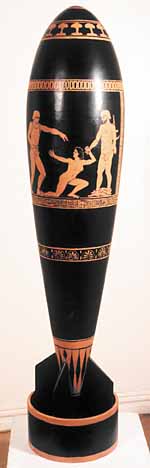

Battleship Crusade, wood, metal, 192" x

56" x 28"

Battleship Crusade, wood, metal, 192" x

56" x 28"Current Issue Highlights More Readings DA Home About Direct Art

Jeremy Eagle: artist in exile

by Barry Thorne

It is late at night. A large, empty, Kafkaesque office building looms above Seventh Avenue in Manhattan. Silently, in a small room on the fifteenth floor, sits sculptor Jeremy Eagle. The entire floor is dark; he is alone. He sits transfixed, barely a muscle in his body moves. Slightly hunched, he gazes into a large computer screen. Only his right hand moves slightly, directing the mouse of the computer. His eyes follow the tiny arrow on the screen, grasping dots on a map, moving roads, placing towns. He has been sitting here for five years now, weary of art. Five years ago he stopped making sculpture and entered this labyrinth world of office towers and publishing houses.

Battleship Crusade, wood, metal, 192" x

56" x 28"

Battleship Crusade, wood, metal, 192" x

56" x 28"

The process, which led Eagle to this room, began at birth in 1955. Born to politically active and radical parents, Eagle’s formative years were filled with political activism. By the age of ten he was attending anti war rallies, an ongoing activity which carried on for ten years through the end of the Vietnam War. This influenced the development of his sculpture, which is based on social and political commentary. Eagle sees this influence stemming back two generations. His grandparents and their siblings immigrated from Eastern Europe and Russia in the wake of intense anti-Semetic persecution. The shock of being driven from their homes and forced to relocate to a strange land on the other side of the globe still reverberates through time. The energy of this tragic journey passed through the veins of his grandparents, into his parents and finally through his hands into his art.

Eagles decision to enter the world of art came at an early age. As a child, he loved to draw. He recalls drawing a portrait of Martin Luther King. The portrait of King inspired him and at that moment he decided to become an artist. He saw the image before him not just as a work of art, but as a political voice, as a vehicle for social change. He decided then and there to dedicate his life to this: political change through the vehicle of art.

On graduating high school he studied art at Cooper Union and then went on to a Masters Degree in Fine Art at the Maryland Institute. He had hoped to land a university teaching position. On graduating he soon discovered that the teaching job was virtually impossible to find. He became, like countless other American artists, a man with a masters degree who did odd jobs, struggling to create his art while paying back his student loans. Fortunately, the vigor and idealism of youth prevailed and the art was made.

Eagle’s art, primarily sculpture, has been described as three-dimensional political cartoon. In some regard this is a fitting description, for there is a lot of humor in the work, but it is incomplete. More than just humorous commentary, his work is direct, bold and confrontational. In one piece for example, the Cathedral Battleship, the artist has sculpted a sixteen foot long scale model of an American battleship. In the middle of the deck where the ship’s towers should normally be sits an intricately carved Gothic cathedral. Battleship cannons jut out the windows. Humorous yes, but with this simple surreal placement of objects a myriad of ideas ensues. Some pieces, such as the movie marquee series, are more singular in their statements. The White House movie marquee is a scale model of the White House, which hangs on the wall like a traditional marquee. Beneath it hangs a crumbling, decrepit chandelier assembled from scavenged plumbing parts and the glowing sign on the side reads in bold letters: "Now Playing: SCAM." Confrontational and defiant, the work hammers out at the viewer with too much force to be labeled mere cartoon.

After leaving the Maryland Institute and the idea of teaching behind, Eagle spent a few years working in Baltimore on a grant from the Maryland State Arts Council. Tiring of the industrial landscape, he traveled to Woodstock, NY. There he spent several years living and working at the Jane Burr House, a now defunct artist residence formerly operated by the Woodstock Artists Association. After Woodstock, he moved back to Manhattan and immersed himself in the New York art world.

Eagles apartment is a fairly large, two bedroom. It is situated in a prewar building at the northern tip of Manhattan in a neighborhood known as Inwood. The apartment has been converted into a sculpture factory. The large living room is the main assembly location; there the work is constructed. The floor has been covered with masonite. Makeshift shelves are loaded with chisels, knives, clamps and glues: the products of manufacturing. The small second bedroom is a power tool room. Padded with foam to dull the noise to neighbors, the room contains a large table saw, drills and belt sanders. The larger bedroom has a bed, but its primary use is as an office and drawing room. Drawing, design and layouts on paper are generated here. The rest of the apartment, kitchen, dining area, foyer, are all used for storage of his works. Numerous objects, collected for possible use in future projects, lay scattered about. The feeling one gets from the space is a combination of a workshop and an antique dealer’s storage room.

For years Eagle worked feverishly in this Inwood apartment studio, exhibiting periodically at various Manhattan galleries. His work was progressing nicely and was beginning to sell. He was in exhibitions at Frumkin Adams Gallery (now George Adams Gallery) on 57th Street in Manhattan and his work appeared in Art In America. His career seemed on the verge of an explosion. Yet at this moment when most artists would be grinning with anticipation, Eagle was enraged. He was frustrated and be

fuddled with a crisis of conscience. It is a crisis that confronts all artists who see their art as a voice and a vehicle for social change. A crisis that occurs when they realize that even if they achieve the status of a Schnabel, their art, the outpouring of their soul, will affect virtually no one. The audience for fine art in the contemporary world is sadly very small. The best an artist can hope for in these conditions is that someone will exchange some money for their art. It will then be taken from them and placed in a storage vault, or in a vacant room of a large country home where no one will see it save a few servants, some kids and the family dog. Perhaps it will be placed in a museum show, or in a magazine. Even there it will be quickly viewed, reviewed and forgotten, affecting virtually no one. It will have less influence on society than the most mundane and profanely motivated TV commercial.

Many artists, when confronted with this reality, continue with their work. Perhaps they see past it to some meaning in the future. Perhaps they have just invested too much of their lives in the pursuit of a vision to accept defeat and forge ahead in denial. Eagle just stopped. He says he may begin again, but for now he sits alone many a night in the office tower, clicking away at the bluish glow of the screen. He says he enjoys the work. Still I can not help but feel, seeing him sitting there in the silent hush of office carpeting with no sound but the whirring of the computer fan and the click click of his mouse, that he is in some sort of self imposed exile, a freakish techno-Siberia. He is not working, he is not at a job. Rather, he is experiencing a deep and lasting penance, a profound metaphysical denial. Tragically, the only witness is a plastic mouse, a whirring fan and a large Styrofoam coffee cup from Dunkin Donuts that sits half empty on his desk.

Contact Jeremy Eagle: jeremyeagle@hotmail.com

Current Issue Highlights More Readings DA Home About Direct Art