|

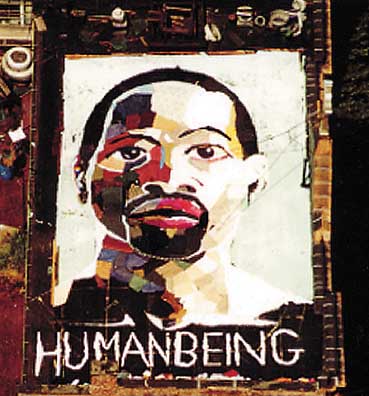

Human Being, created in 1999 on the roof of St. Agnes Church in Manhattan from the discarded clothes of the homeless, 65 x 35 feet. |

Steve Cosentino, Human Being

by Tina Stave

|

Human Being, created in 1999 on the roof of St. Agnes Church in Manhattan from the discarded clothes of the homeless, 65 x 35 feet. |

Steve Cosentino, who lives and works in New York City, paints with the circumstances of others in mind.

The Human Being came about in protest to the what the artist thought was a raw deal: The Grand Central Neighborhood Social Services Corporation, a non-profit agency, had been running a service center out of a former high school for boys owned by the St. Agnes Church. Grand Central had been helping hundreds of homeless adults in the Midtown area from this service center, the largest of its kind in the country, since 1989. It had also provided space on its sixth floor for Mr. Cosentino’s use as a studio. But in 1999, its landlord, the St. Agnes Church, notified the non-profit that, in order to make way for a multimillion-dollar apartment building, it had sold the building including the air rights above it and that the agency must leave immediately. There was little regard for the people being served.

Upon hearing of this injustice, Mr. Cosentino went right to work. In his largest and most well known mural, measuring 65 by 35 feet, Cosentino produced with discarded clothing from the center the portrait of a homeless man, entitled Human Being. Although the mural would exist for just a few months before the building would be demolished, that was long enough for the Human Being to be noticed by more than just those people in the surrounding community whose offices looked out onto the roof of the six story building. The New York Times and other media picked up the story of displacement.

"People got to take a look at what was going on with regard to homeless people in midtown," Cosentino said. "Maybe some people’s consciousness got raised a little bit by caring about people who were much less fortunate than they were. That was the whole idea."

|

Human Being Dismantled The church cashed in its chips, trading the house of worship and homeless shelter for forty five million. |

Once the building was vacated, the church moved to remove the work of art. It’s destruction of the mural created a strange, haunting image in shades of black. First, the clothing was removed, and then the next day the highlights were covered with black paint. But no avail. In black relief then, the face was still visible—representing and emphasizing a desire to cover up the problem of homelessness with purely cosmetic tactics.

For Cosentino, creating socially conscious work means revealing underlying attitudes that value real estate or enterprise over caring for those in obvious need. "I think that we need to raise our level of consciousness by taking care of our fellow human beings," he said, "even extending further out than this country."

Through his work Cosentino points out injustice and social disparity in order to prompt the viewer to action. He received formal training at the Art Students League from Rudolf Baranik and went on to teach there, taking Baranik’s class for a semester. However, real life has been his best teacher.

"Yes, I went to classes," Cosentino said. "But with art as with anything else in life, it’s mostly self-learning. Really, I learned by doing."

Showing his work in New York galleries in the 1980’s and 1990’s, Cosentino had been doing socially minded work long before he partnered with Grand Central Neighborhood. However, his relationship with the center vastly changed his art in the late 1990’s: He expanded his media past his favorite traditional oil on canvas to include house paint on walls.

His first murals for the Grand Central Neighborhood were the fifteen painted on the walls of the old social services center. Those of Bryant Park, familiar to many of the clients before its renovation, were welcomed and uplifting. The people identified with the specific scenes and were in effect back in the park that had been the occasional to frequent home of many.

And while Mr. Cosentino was soon painting murals in restaurants and other businesses, his work on behalf of the homeless was not finished. He has helped procure socially conscious art for display in BIGnews, Grand Central Neighborhood’s literary monthly street magazine -which features outsider art and writing.

|

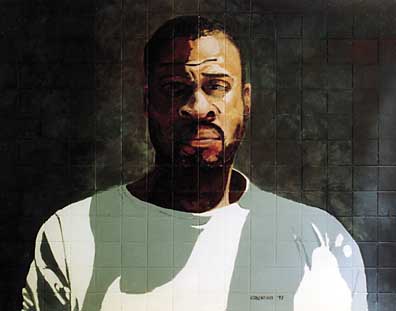

Roper, a 10 x 11 foot acrylic mural on a concrete block wall was also among the works destroyed. |